Relief Channels and Re-Meandering to Mitigate Flooding

Floods can devastate cities, but what if we fought water with nature instead of just concrete? While relief channels redirect raging rivers, a quieter revolution is unfolding: re-meandering rivers to slow floods, restore ecosystems, and rethink how we shape the land.

When we think of flood control structures, the first things that come to mind are likely sturdy dams jutting out of the countryside, or long embankments supporting a bustling city centre. However, there are subtler ways hydrologists and engineers can nip a potential flood in the bud.

Rivers facilitate trade and communication, and many cities grew to their current sizes from small riverside villages. River floods, however, are a major challenge to any city. They are especially problematic if unpredictable meltwater or seasonal rains form a major part of the river’s discharge, making this disruption a potentially yearly occurrence.

One way to mitigate this risk is to reroute the water elsewhere by digging concrete-lined channels. These are split into two types: bypass channels and diversion channels. Bypass channels are connected to the same river system at both ends and usually skirt around a densely populated area. When water levels are high, these channels carry floodwater to the countryside downstream, where the water rejoins the river. Diversion channels do not lead back to the same river system, either going directly out to sea or into another drainage basin. When a flood occurs, sluice gates in a dam are opened or closed to redirect water from the main river to the relief channel.

Relief channels are immediately effective after construction and can be expanded if necessary. Disregarding the control structures at either end, they only occupy a narrow strip of land. But they are not a silver bullet against flooding. After all, they cannot make water disappear, only take it elsewhere. Furthermore, they can overflow if there is not sufficient capacity.

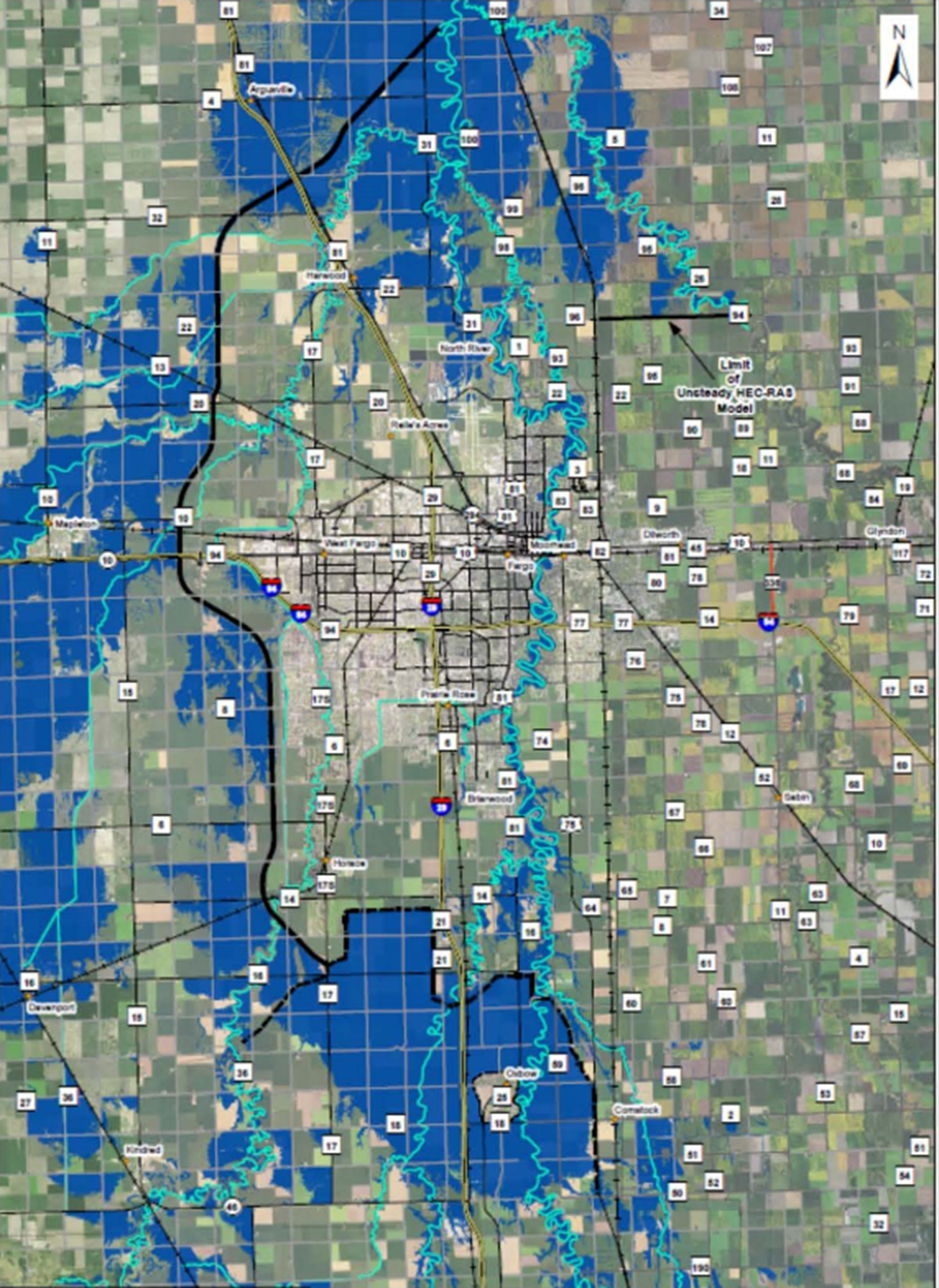

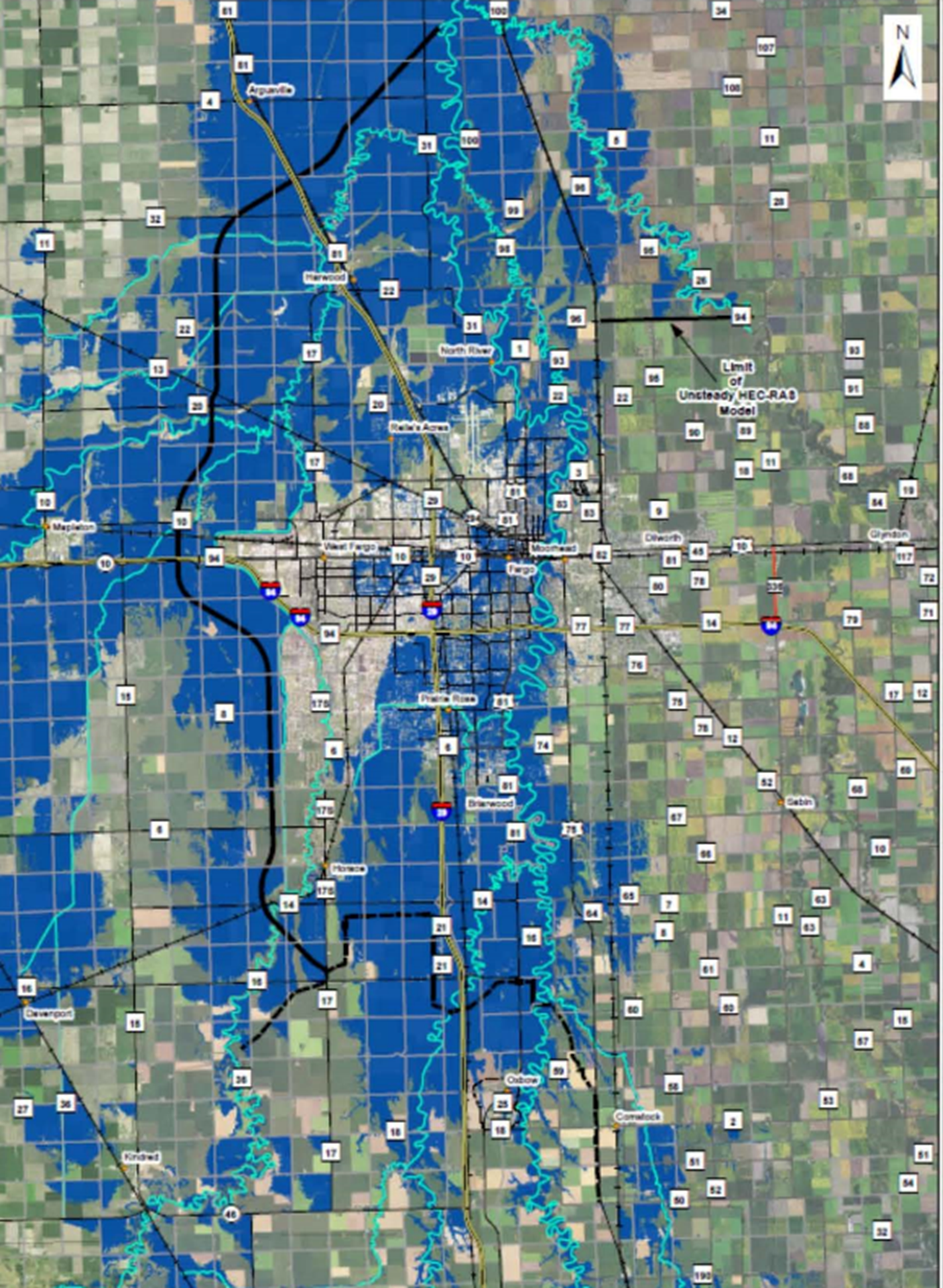

Left: With flood defences; Right: Without defences. Blue represents areas at >1% risk of flooding each year. Flood defences protect the city at the expense of the surrounding countryside.

Bypass channels are a logician’s solution to the trolley problem, with the wave of floodwater being just as unstoppable as the original trolley. By redirecting a flood from a populous city to the surrounding countryside, evacuation is easier and financial damage is minimised. Towns and cities downstream had better also have a bypass handy, as the same amount of water is headed toward them. The official deciding whether to open a diversion channel faces much the same dilemma: this time it is another river, with all the towns and cities lying on it, that would be threatened.

Is there a better way? As it turns out, the answer lies not in building but in restoring.

Every geography classroom in the world probably has the word “oxbow lake” printed on at least two walls. These lakes form and dry up in a cyclical process. A straight river on a relatively flat floodplain will deposit sediment unevenly, creating meanders. The neck of the meander narrows, and the river eventually breaks through it, returning to a straighter course. The detached meander becomes an oxbow lake. Without interference, nature reaches an equilibrium, and the river has a mix of straight sections, wide and narrow bends, and oxbow lakes.

Humans, however, have systematically cut off meanders from rivers: some, such as the Mississippi, are hundreds of kilometres shorter than they used to be. Early modern planners straightened rivers to increase productive land area, shorten travel times, and facilitate shipping. They also reinforced their banks with hard impermeable materials, such as stone and brick, to reduce erosion and ensure the river stays on the modified course. These two processes are collectively known as channelisation: the confinement of a waterway to a modified, reinforced course.

The benefits of channelisation are real, but so are the unforeseen downsides. Straightening rivers prevents local flooding by allowing water to flow through fast and unobstructed, but it also worsens the situation downstream: it is exactly fast and unobstructed water that will cause flash flooding when it spills over the banks.

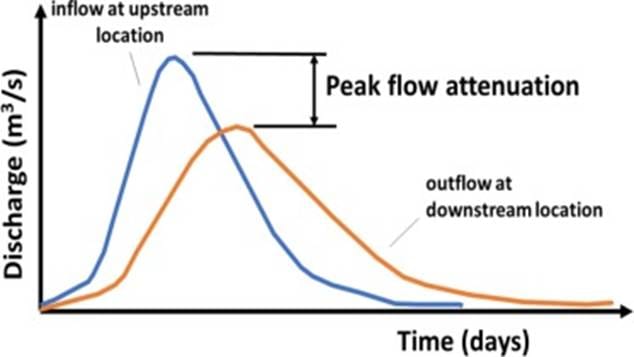

What matters in a flood is not the total volume of water – it is all about how quickly it arrives. This is why a few hours of heavy rain can inundate streets, even though the same amount of water spread out over a few days would drain with no ill effects.

Many rivers are not used for navigation anymore, making channelisation obsolete. With the benefits of meanders now fully known, government agencies and organisations have been undoing channelisation works, a process known as re-meandering.

The first step to re-meandering a river is knowing where it used to flow. If channelisation is recent, the old channel may still exist. If not, they can consult historical maps to reconstruct it. If the original course is completely unknown, then hydrologists survey the area to find a plausible and sustainable path. Planners often run computer simulations to investigate the impact of different routes on the frequency and severity of flooding. After the course is determined, the river is coaxed into it. Old dams are demolished; the original meanders may be widened or deepened to stop sediment blocking them; the straightened channel may be dammed or allowed to carry a small amount of the flow.

Restored meanders slow down water flow. When a flood occurs, this reduces its peak flow rate, which lowers its maximum height. Additionally, water has more time to be absorbed into the ground. If the river is allowed to overflow onto a floodplain, vegetation will slow it down further. Other advantages of re-meandering include ecologic revitalisation and better appearance.

On the other hand, releasing a river from human control can have unintended consequences. After re-meandering, rivers gradually change course by eroding its banks. Erosion is especially rapid immediately after project completion, because the new banks lack plant life to hold soil in place. If this is undesirable (for example, if that section of the river flows next to buildings), protective rubble can be placed to slow erosion, but this increases the cost of the project. Re-meandering also takes more time to show results, as vegetation may not establish itself for a few years after the river changes course.

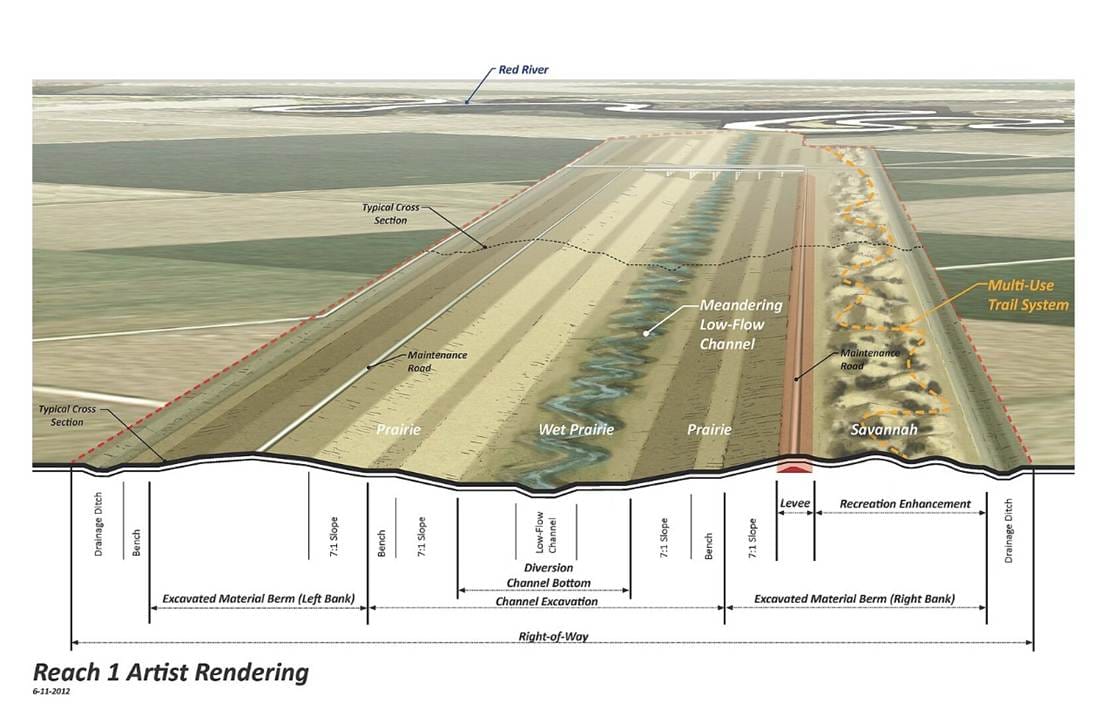

Relief channels directly lower flood levels, while meanders provide long-term hydrological and ecological benefits. Some flood mitigation projects combine them. The Fargo-Moorhead Area Diversion Project on the North Dakota-Minnesota border, guarding against the flood-prone Red River, is one example. Although it is an artificial drainage channel capable of sustaining a large flow capacity, its low-flow channel includes meanders to slow down water passing through. This way, it can sustain high flow rate during a flood, as well as support local wildlife when conditions are normal.

Relief channels and re-meandering are complementary solutions to the problem of flooding. Relief channels show their strength in urban areas, where space is limited. By contrast, re-meandering works best in rural areas, where there is more expendable land to work with. In a changing climate where many areas become vulnerable, relief channels and re-meandering are two useful approaches that should have their benefits and drawbacks carefully considered before implementation.