The Mental Factors of Ageing

Legacy articles aren't reviewed and may be incorrectly formatted.

The Mental Factors Of Ageing

Jonathan Zhao

Introduction

From Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s frantic quest for immortality to the myriad of cosmetic products that fuel modern consumerist desires, the implications of ageing with death and decline see a surging attempt to understand as well as counteract this phenomenon. Only in the past century, however, has the growth in physiological understanding unlocked a scientific explanation. First, there is a strong contiguity between our mental and physical state: our thoughts and emotions are not the voices of an inner spirit, but rather the accumulation of electrical and chemical signals within the neurons of our brains. Ultimately, these cells suffer the same physical decline as body cells. Second, ageing is characteristic of a concurrent regression of mental and physical capabilities. The more apparent changes - the wrinkles and greying hair - happen in tandem to the onset of neurological conditions, such as dementia. It is impossible to detach from the physiological changes as we age, but the incorporation of the psychological progressions plays an important, albeit symptomatic rather than causal, role.

Physiological Causes

The 20th century paved way for technology to advance medicine and for science to provide explanations for observations. The 1980s saw the first tangent drawn between genetics and ageing, where Elizabeth Blackburn’s [1] Nobel Prize winning work outlined the importance of telomeres in cell survival and function. During cell division, genetic data is lost when nucleic acids struggle to bind to the template strand. Telomeres are repeated sections of DNA at the end of chromosomes, whose presence protects the remainder of the gene. Over numerous cycles of cell reproduction, telomeres are whittled down; the cells enter a “senescence” phase where they do not divide; cell death quickly ensues. For example, the inability to replace elastin and collagen fibres in the dermis of the skin promotes wrinkled skin in elderly people [3]. This is exacerbated by the accumulation of DNA damage - whether through oxidative stress, carcinogens, or UV light - that is passed on from cell to cell [7].

Most cells plateau in efficacy once they selectively express genes and form “specialised cells”, be that to make up muscles, skin or nerves. Uniquely, stem cells can divide and differentiate into other cells, replenishing worn out ones. In embryos and children, stem cells are omnipresent, hence the amplified ability for their wounds to heal. However, ageing necessarily sees a dwindling in the arsenal of stem cells, where even the remaining few (in the bone marrow) are multipotent as opposed to pluripotent, losing the ability to differentiate into all specialised cells and only able to conform to a few. It is the unity of these factors, a simultaneous acceleration of atrophy conjoined with the incompetence of reparation, that piles the cornerstone behind the physical changes characteristic of ageing [8].

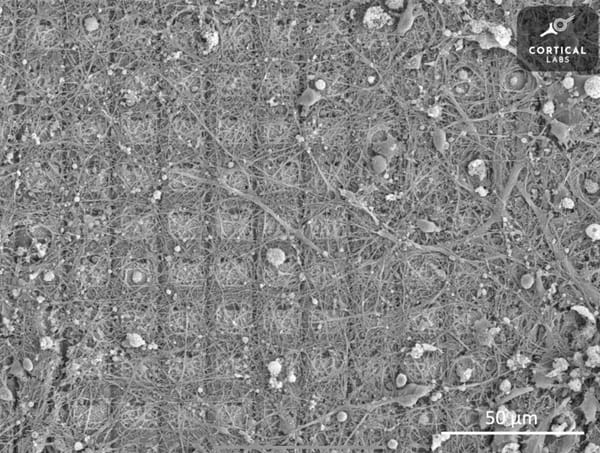

The mental changes are similarly substantial. Neurodegeneration plagues the elderly population, with 55 million global patients [11]. Even though its prevalence misconstrues it as synonymous to normal brain ageing, there are differences. The latter is seen by slight reductions in cognitive ability: a loss in semantic memory, reduced ability to multitask, and weakened affinity for neurotransmitters. On the other hand, drastic physical abnormalities lead to conditions we characterise as dementia - symptomatic of severe memory loss, cognitive impairments and eventually, death. At its root, brains of Alzheimer’s patients exhibit aggregation of Aβ and τ neurofibrillary tangles[2], abnormal proteins that build up in one's neurons; Parkinson’s Disease spawns from neuronal death in the substantia nigra that impede dopamine production[4]. Research highlights a strong genetic influence: mutations within the Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP) or Presinilin (PSEN) gene - encoded at birth – pushes one towards this fate.

We all empathise with the deprivation of memory as much as the crumbling of the body. Some feel that loss, where windows of memory disintegrate into a tessellation of broken shards. The visceral sensitisation of ageing is perhaps the most powerful battle our mental wellbeing can face, but it ultimately draws its roots from a physiological and physical degeneration as well.

However, the explanation why ageing varies so vastly across a population remains unclear when viewed from a purely cellular perspective. Perhaps the way we feel - joy, regret, despair - is cardinal in differentiating the way our bodies and minds play out over time.

Psychology Causes

To accept the significance of mental causes complements the existing understanding and provides comprehensible explanations - not shoved under the rug of ”genetics” - of the difference in ageing observed. No doubt, variety in the feelings we face translate onto how our body and brain evolve.

Stress is of paramount importance in catalysing ageing. The graphics of investment bankers and corporate lawyers greying and thinning as insomnia and caffeine overdoses take their toll are widespread. That cannot circumvent biology. Stress is mediated by the Hippocampal-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, releasing cortisol[12]. This promotes activity of the amygdala, prioritising fear and anxiety related emotions as opposed to rational thought in the hippocampus. The high presence of cortisol not only shrinks the hippocampus and causes severe depression down the line, but also leads to ”unsuccessful ageing”, where neurological disorders become prevalent and cognitive decline speeds up. Similarly, depression and anxiety are correlated with disorders, such as stroke (through artery blockage) and multiple sclerosis (through inflammation of brain tissue).

There is a causal mismatch here, however. Perhaps our body appears to grow older as a result of the cortisol from stress, but that in itself is a footprint of mental factors derived from both inner psychology and social influence. Because of social media, we are compelled to set unrealistic expectations on an already arduous life, the failure of which leads to strain and stress, fast-forwarding the ageing process.

Simultaneously, the zero-sum positions and wealth which unlock those desires are increasingly saturated. Depression rates skyrocket as more people feel alone despite the technological interconnecity[6]. Most bodies deteriorate fast, faster under that mental strain. Conversely, the abundance of positive emotions in and of itself - happiness and hope - sees at least a correlative effect on slowing ageing [10]. This is because normal levels of cortisol and noradrenaline, the stress hormones and neurotransmitters, are desirable and enhance cognitive ability. The fair distribution in binding on low MR and high GR receptors optimise hippocampus function.

Beyond the direct ramifications of mentality on biology, there are indirect routes that are equally powerful. The brain influences our daily actions: the cerebellum directs our voluntary movements after the prefrontal cortex dictates choice. It is those actions that cumulate into our lifestyle, which ultimately enhance or disharmonise the tune of ageing. Indeed, studies conducted by Samarakoon et al. [9] outline the importance of healthy diet in normal ageing, where the lack thereof exacerbates symptoms. Psychology is of utmost importance here. From addictions to dopamine and serotonin that are only satisfied by indulging in substances like cocaine, to social ”peer pressures” from fear of missing out that cause alcohol overdoses, the choices and the reaction one has towards their surroundings build up that lifestyle that heavily impacts the ageing process[5]. In the effort to satisfy our mental desires - to dampen pain (alcohol) or maximise pleasure (drugs) - physical compromise becomes habitual and overrides the genetic dispositions we may have in bodily decline.

Conclusion

There is no comparable feeling of nostalgia than when we see a picture of a grandparent. It may be crumpled, yellow and eroded; but they give off a youthful radiance that only hyperbolise the effect of ageing and the fear we hold it to. Even though we recognise it as inevitable, the social stigma around ageing is unfair. The awe towards elders, prevalent in Ancient Greece, is waning, where rhetoric paints the older generation with contempt as much as respect as stereotypes of futility and decline kicks in. We fear it.

Still, the stem cells deplete themselves and the telomeres dissipate; sight blurs and sound deafens; skin loosens and joints crack. Mental factors are just as significant in ageing: they exacerbate the cellular interactions behind its onset and progression; they influence the way we choose to walk the path of life, and hence the direction, length, and the backdrop. The observable changes are the phenotypes of a cellular or genetic malfunction, which may be more likely to happen in some people rather than others. However, when society infiltrates our thoughts and actions. torrential stress and deadly habits override those tendencies in place. To understand the mental factors are perhaps more important, as observable and controllable omens for the future

Physical factors mean ageing happens, mental ones determine how and when.

References

- Elizabeth H Blackburn. “Structure and function of telomeres”. In: Nature 350.6319 (1991), pp. 569– 573.

- Zeinab Breijyeh and Rafik Karaman. “Comprehensive review on Alzheimer’s disease: Causes and treat- ment”. In: Molecules 25.24 (2020), p. 5789.

- Jean Calleja-Agius, Yves Muscat-Baron, and Mark P Brincat. “Skin ageing”. In: Menopause interna- tional 13.2 (2007), pp. 60–64.

- Julian M Fearnley and Andrew J Lees. “Ageing and Parkinson’s disease: substantia nigra regional selectivity”. In: Brain 114.5 (1991), pp. 2283–2301.

- Chester County Hospital. The Facebook Effect: How Is Social Media Impacting Your Stress Levels? url: https://www.chestercountyhospital.org/news/health-eliving-blog/2020/march/how- is-social-media-impacting-your-stress-levels.

- Kelly G Lambert. “Rising rates of depression in today’s society: consideration of the roles of effort- based rewards and enhanced resilience in day-to-day functioning”. In: Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 30.4 (2006), pp. 497–510.

- Lawrence J Marnett. “Oxyradicals and DNA damage”. In: carcinogenesis 21.3 (2000), pp. 361–370.

Thomas A Rando. “Stem cells, ageing and the quest for immortality”. In: Nature 441.7097 (2006),

pp. 1080–1086. - SMS Samarakoon, HM Chandola, and B Ravishankar. “Effect of dietary, social, and lifestyle determi- nants of accelerated aging and its common clinical presentation: A survey study”. In: Ayu 32.3 (2011), p. 315.

- Andrew Steptoe, Angus Deaton, and Arthur A Stone. “Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing”. In: The Lancet 385.9968 (2015), pp. 640–648.

- WHO. Dementia. url: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia#:~: text=Key%20facts,injuries%20that%20affect%20the%20brain..

- Rachel Yehuda. “Biology of posttraumatic stress disorder”. In: Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 62 (2001), pp. 41–46.