Nerves, Pain, Dr Seuss, and the Chippendale Mupp

Although hypothetical and a little absurd, for a story written in 1962 the Chippendale Mupp can prompt all sorts of questions and calculations about the technicalities of nerves.

Legacy articles aren't reviewed and may be incorrectly formatted.

Nerves, Pain, Dr Seuss, and the Chippendale Mupp

Oscar Lawson

In a childhood favourite book of mine, Dr Seuss’ sleep book, we meet, among other dozy creatures “In the valley of Vail”, a “Chippendale Mupp”. In the epitome of Seussian wit, we learn that the Mupp, lacking an alarm clock, bites his tail before going to sleep. It takes so long for him to feel the bite because his tail is so long, that he gets a full 8 hours sleep before being rudely awakened by the pain.

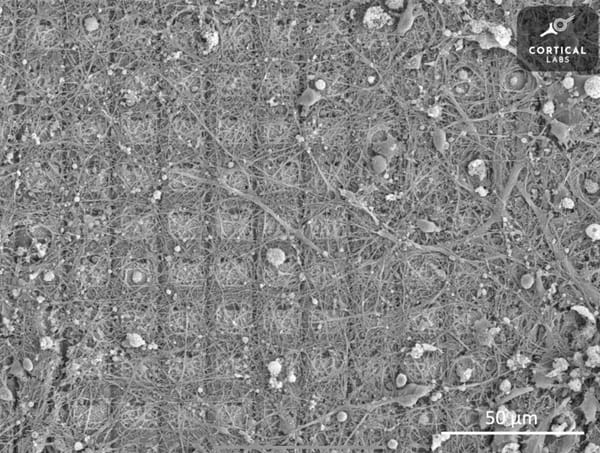

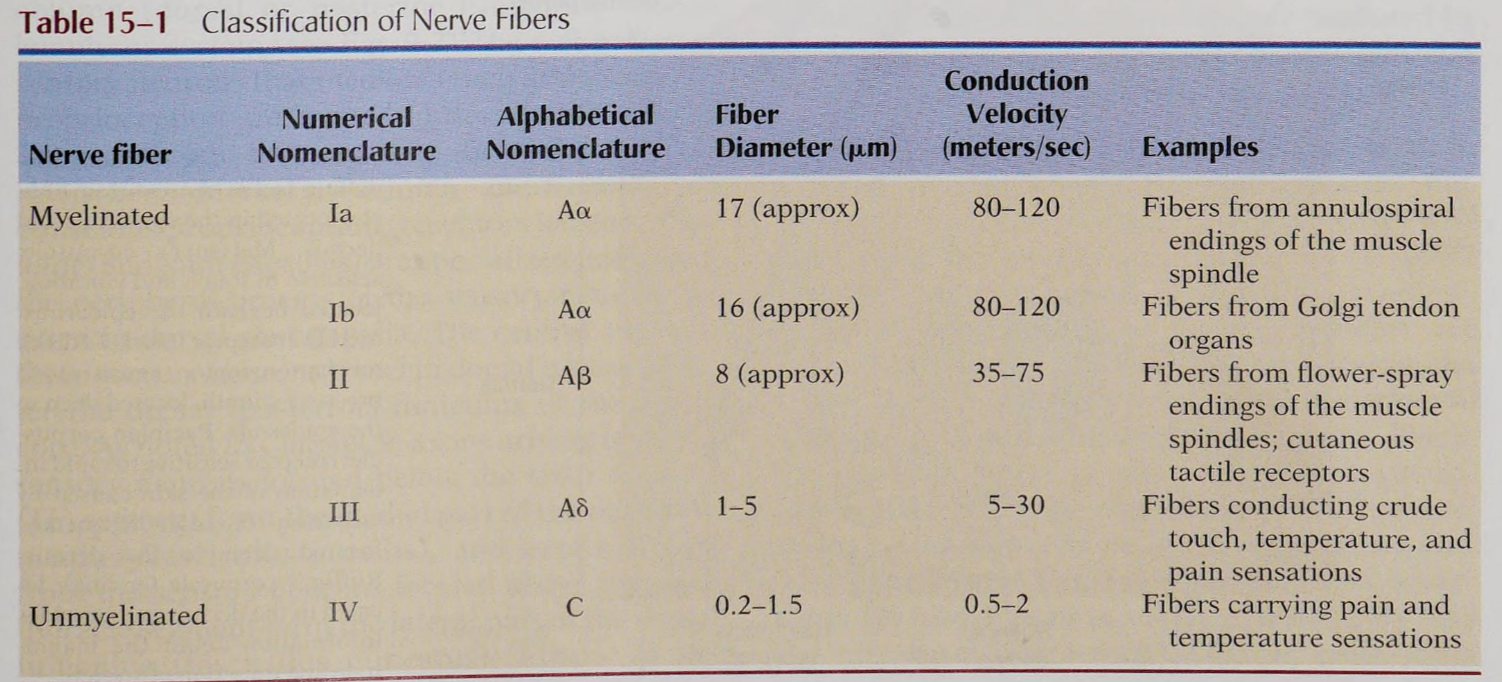

Ignoring the practicalities of how he could possibly control a tail with such length, I recently wondered how long the Chippendale Mupp’s tail must actually be. Taking this biologically, different nerves have different properties, but all of course take some time for impulses to travel along them. All nerve signals travel significantly slower than electricity, and one has to build in the time for chemicals to cross synapses between nerves. With this taken into account, the fastest nerve signals travel at up to 120m/s, specifically the nerves for proprioception and detecting muscle tension changes. These nerves are myelinated, with an insulating sheath of proteins and fatty acids, allowing faster transmission of signals.

“Crude” nerve fibres detecting touch, and cold temperatures as is now understood, conduct at a velocity of 5-30 m/s with their thin myelin sheaths, and unmyelinated nerves carrying pain sensations conduct at only 0.5-2 m/s. This may seem slow, at 240 times slower than the fastest signals, but on the human scale of a few metres of nerves maximum from receptor to brain, this is unnoticeable.

Now, to the Chippendale Mupp…

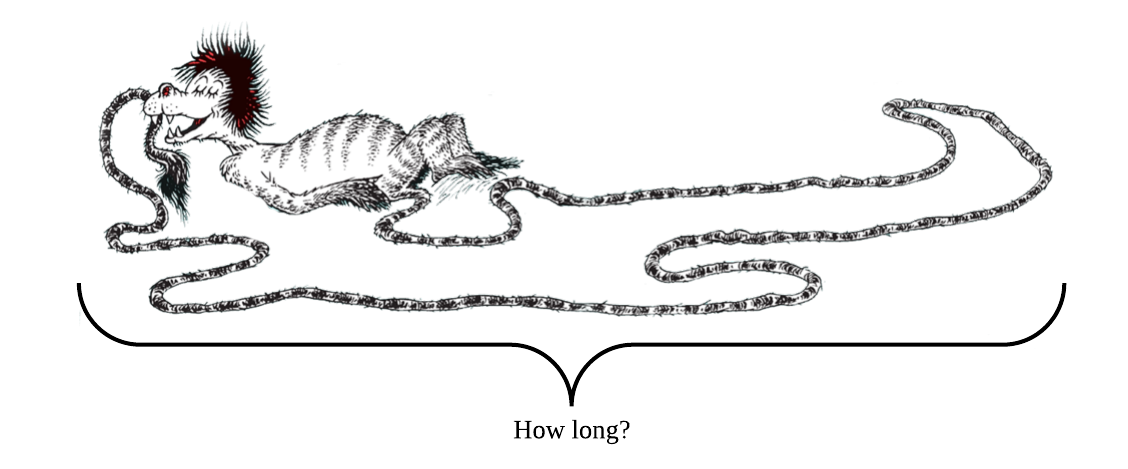

Slow nerve conduction velocities are actually to the Chippendale Mupp’s advantage here, so its tail doesn’t have to be as long to take the same amount of time to conduct the pain signal. So, let’s assume the tail of the Chippendale Mupp has pain receptors sending signals at 0.5m/s. For 8 hours of sleep, one needs the impulse to travel for 60*60*8 = 28,800 seconds. At the slowest 0.5 m/s, the Mupp’s tail would still need to be 14.4km long! Quite an appendage to lug around with him.

What’s interesting about the different nerve speeds is that the Mupp may well feel the touch of his teeth on his tail sooner than the pain, because the thinly myelinated touch nerves conduct signals at 5-20m/s. So with the fastest nerves, the Mupp could feel the touch after 14400/20 = 720s or 12 minutes, but not realise the actual pain until 8 hours later.

Pain reception is clearly vital for survival, and doing so in a timely manner is essential. If the Mupp left its tail in a fire, it may not notice for minutes or even hours, risking permanent damage, and even once moved out of the fire, the excruciating pain would continue for that same length of time.

Although hypothetical and a little absurd, for a story written in 1962 the Chippendale Mupp can prompt all sorts of questions and calculations about the technicalities of nerves.

Conclusion: given the choice between a 14.4km tail and buying an alarm clock, the Chippendale Mupp should wish evolution had invented electronics a bit sooner.

[Siegel, Allan, and Hreday N. Sapru. Essential neuroscience. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006, pg 257]