Hydrogen Cars

Hydrogen powered cars present a sustainable transport alternative to electric cars. However, there are many questions to be answered: are they more environmentally friendly? Are they economically viable?

Introduction

Hydrogen fuel cell powered cars seem to be the next step in renewable and green transportation, replacing traditional fossil fuel based vehicles. While most of the focus so far has been on electric vehicles, hydrogen powered cars present an exciting and futuristic opportunity. However, car companies (in particular East Asian manufacturers) haven’t invested time or money just because it sounds cool; Hydrogen offers several advantages over petrol, diesel, and even electric vehicles. However, it’s also important to understand the challenges that hydrogen cars face in order to advance the technology further.

History

The first fuel cell was created by William Grove in 1838. After he and others refined the initial idea, hydrogen fuel cells became an efficient way of producing power. Hydrogen splits at the anode into an electron and a proton. Then, the proton passes through the electrolyte to the oxygen being supplied to the cathode. The remaining electrons pass through an external wire, where their energy can be harnessed, and then at the cathode water is produced.

In 1932, Francis Bacon developed the first practical alkaline fuel cell. In these fuel cells, the electrolyte is alkaline and the hydrogen splits into protons and electrons by reacting with the OH- ion. At the cathode, the OH- ion is reproduced by the oxygen, and the flow of electrons from anode to cathode produces the energy.

\[2H_{2} + 4OH^{-} \to 4H_{2}O + 4e^{^-}\]

\[O_{2} + 2H_{2}O + 4e^{-} \to 4OH^{-}\]

\[Overall: 2H_{2} + O_{2} \to 2H_{2}O\]

Environmental benefits

As you can see, Hydrogen fuel cells have only one waste product: water.

This is environmentally much better than a petrol cars that emits carbon dioxide. While both water (in its gaseous state) and CO2 are greenhouse gases, excess water vapour that we let into the atmosphere will come down as rain before it can make a noticeable impact on our planet’s greenhouse effect.

3.53 billion tonnes of CO2 are released by cars and vans every year[^(statists.com)]

41.42 billion tonnes of CO2 are released by human activity every year[^ourworldindata.org]

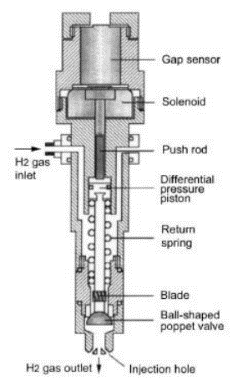

Storing and transporting hydrogen

Hydrogen has a very low density, so transporting it in its normal gaseous form is incredibly inefficient.

One of the advantages hydrogen has is that more energy is released per mole compared to petrol and diesel. Hydrogen has an energy density of 120 MJ/kg compared to Diesel’s 45.5MJ/kg and petrol’s 45.8 MJ/kg[^rmi.org]. However, the space required for this hydrogen means that there is much more chemical energy in a tanker of petrol than a similarly sized tanker of hydrogen. Therefore to make the transport of hydrogen efficient, it either needs to be stored at very high pressures, or very low temperatures. Mostly, hydrogen is transported as a liquid. The boiling point of hydrogen is -253 degrees Celsius so it has to be stored at a lower temperature than that. This process is costly and uses up 30% of the energy that can eventually be made from reacting the hydrogen[^US Department of Energy]. The technology to store such cold hydrogen and transport is expensive as well. While richer countries may be able to afford specialist trucks and cooling facilities in the name of environmentalism, poorer countries may decide that the investment isn't worth it for them, turning them to petrol.

Hydrogen vs Electric

Anyone who has an electric car is probably aware of how short their range is compared to petrol or diesel cars. That, combined with the lack of charging sites, is possibly the main advantage of traditional combustion engines. While finding a place to refuel your hydrogen vehicle is an even bigger problem than for electric cars, this could become less and less of a problem as they become more mainstream. Comparing the range of hydrogen and electric cars, the only publicly available hydrogen fuel cell car to buy is the Toyota Mirai, which has a range of 400 miles. The only electric car that has a better range is the Mercedes EQS 450[^ev-database.org] and this car costs nearly twice as much as the Toyota. As hydrogen technology advances, hydrogen vehicles might be able to challenge petrol cars in popularity for long range journeys.

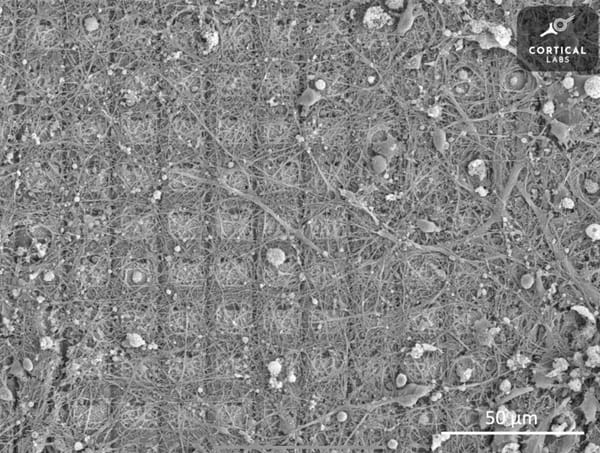

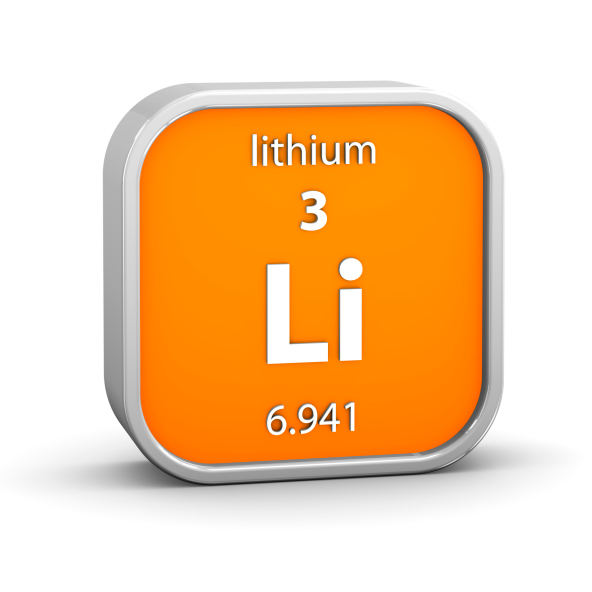

Both hydrogen and electric cars are ‘zero-emission’, but there is increasing awareness of the actual damage to the environment caused by the manufacture and disposal of electric car batteries. Manufacturing electric cars uses 8kg of lithium per car [^Argonne National Laboratory]. Each tonne of lithium extracted uses 2.2 million litres of water[^greenly.earth] so over 17000 litres of water per car. Furthermore, 8 tonnes of CO2 is released for every electric car during its manufacturing[^Earth.org].

Toyota claims that the aforementioned Mirai’s lifetime emissions are 90% of hybrid petrol-electric cars (although they don’t provide much evidence for these claims). Their website also provides figures for the emissions of hydrogen production in a hypothetical world where all hydrogen is produced from electrolysis powered by renewable sources. In this ideal future, the emissions of the Mirai across its lifetime would be under half that of a hybrid petrol-electric car. It’s worth taking these figures with a pinch of salt as they have deliberately avoided comparing their car to a fully electric car and rather than comparing the CO2 emissions directly they use a ‘CO2 index’. It’s also unlikely that hydrogen production will ever get up to 100% sustainably produced. The fact remains that hydrogen cars don’t require lithium, solving what is the possibly the largest environmental issue associated with electric cars.

Safety concerns

Hydrogen is highly flammable, especially at the high pressures needed for fuel hoses to quickly transfer it. Petrol is also flammable (as that is how we extract energy from it) but it needs high temperatures to react. In contrast hydrogen will react quickly when in air, so hydrogen cars need to ensure that no air can get into the car’s fuel tanks or mix with hydrogen before it’s added to the car. While petrol can be added to a car with a normal nozzle, hydrogen nozzles must create vacuum seals to stop any of the outside air entering. It also necessitates more safety precautions at fuel stations, this takes more space than a petrol station and may require specialist training for those who work there or drive the vehicles.

However, potentially the largest obstacle in relation to safety is not the equipment or precautions, but instead changing public perception. For example, nuclear power is actually one of the safest ways of producing energy. It is estimated that only around 0.2 people per million per year would be die prematurely as a result of nuclear power plants in a 100% nuclearly powered Europe, while a 100% oil powered Europe could kill as many as 120 people per million per year[^ourworldindata.org]. However public perception of nuclear power is heavily influenced by a few notable disasters. We already have the ability to keep hydrogen power safe, but its reputation of being ‘highly flammable’ may put off many people from purchasing a hydrogen powered car.

An optimistic future

Alkaline fuel cells, despite being the most used fuel cell for the last 90 years, are now rarely used in vehicles. They have been replaced by proton exchange membranes fuel cells (PEMFCs). They have existed for many years, but were initially shunned in favour of alkaline fuel cells. However, research continued and they have now surpassed alkaline fuel cells. Since their use is fairly recent and rapidly increasing, it is likely that there will still be large gains in the technology. For example, there were three times as many PEMFCs used by Toyota alone in 2016, than the worldwide use just two years earlier[^green carreports.com]

I firmly believe that investment would lead to the mainstream adoption of hydrogen technology. The example provided by the huge change in the amount of electric car infrastructure and the mindset of consumers over the past years should be encouraging to car manufacturers that hydrogen vehicles could follow a similar path. The question remains about whether hydrogen will be better environmentally and economically than the alternatives.