Computing With Life

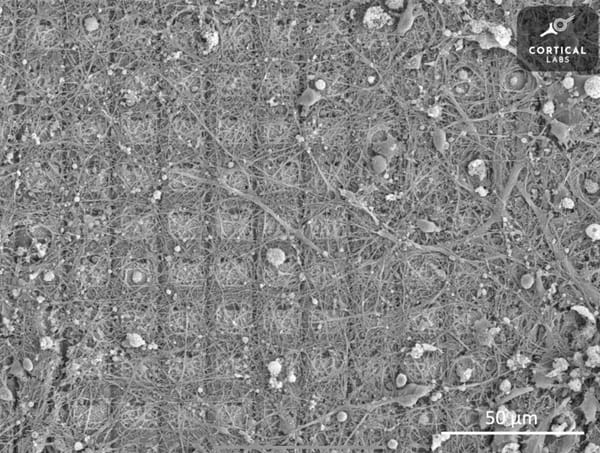

A cluster of living neurons grown in a dish has learned to play a video game. This emerging field of biological computing may change how we think about intelligence itself.

The same processes that power artificial intelligence also exploit human psychology - here's the hidden truth about social media algorithms. The fundamental human desire to seek enjoyment often conflicts with our daily exposure to feelings of boredom and a lack of motivation. This dilemma has greatly contributed towards

Biology

Rising stimulant use among young adults raises a vital question: what do these drugs really do to the brain? This article uncovers how substances like cocaine, and even caffeine, rewire emotion, motivation, and control, revealing how short-term highs can leave lasting marks on the mind.

The news has recently been filled with stories of Donald Trump’s 2nd state visit to the UK, the first time any US president had been invited for a second visit. Over roughly 24 hours from his arrival on the 17th of September to the morrow, he was entertained with

Have you ever wondered how your brain really functions—your thoughts, your memories and how we, humble humans, can achieve the feats we do? Well, wonder no longer, as this article will unveil how memories and emotions are created through phenomena such as active potentials and more

Hydrogen powered cars present a sustainable transport alternative to electric cars. However, there are many questions to be answered: are they more environmentally friendly? Are they economically viable?

Imagine being told that the same useless numbers which you consistently label as redundant in the real world are in fact key to keeping your data safe from prying eyes. Every time someone sends a message, numbers keep your information safe and hidden so only the receiver can see it.

The Rubik’s Cube is far more than a colourful toy—it is a mathematical marvel that embodies the beauty of symmetry, structure, and problem-solving.

The natural world is filled with complex and unpredictable phenomena, from weather patterns to the dynamics of ecosystems and the stock market. At first glance, these systems may seem entirely random, yet there are often underlying deterministic laws governed by mathematics.

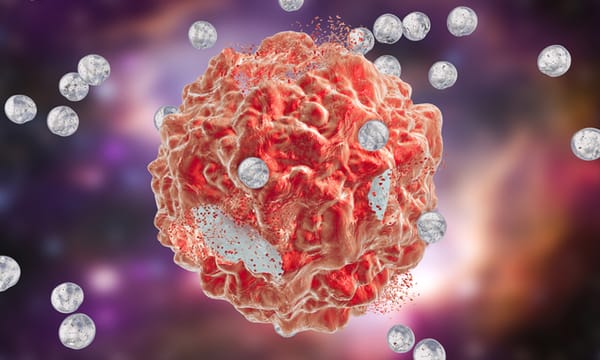

Take a deep dive into the growing role of Nanotechnology in Medicine, and learn about the complex technologies being developed.

Discover the latest developments in Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths for all levels from the boys of Eton College.

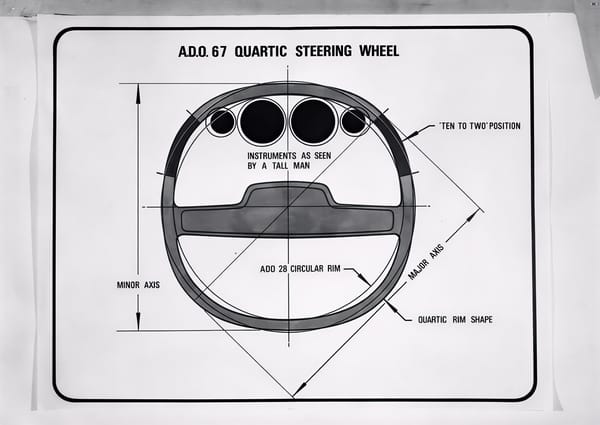

From flop to the top. What the once-mocked square steering wheel and electric glasses can teach us about technological innovation.

It has been pitched as everything from humanity’s ‘backup’ planet to Elon Musk’s future retirement home. For decades, the concept of humans living on Mars has been a topic of interest whether it's between space scientists, sustainability experts or even science-fiction writers. SpaceX openly talks about

At some point during the 12th and 13th centuries, warfare and history in general were changed forever. The first cannon was invented in China, likely based on an earlier gunpowder weapon known as the fire lance. The technology spread all around the known (at the time) world. The design was

In a world that is constantly seeking new and innovative solutions, scientists, engineers, and designers are turning to an unexpected source of inspiration: nature itself. Biomimicry, the practice of learning from and mimicking the strategies found in the natural world, has driven breakthroughs in everything from architecture and medicine to

As decades go by, the common sources of energy, like coal, fossil fuels or natural gases, are coming to extinction. While renewable power plants like wing turbines or solar panels can be used to extract energy, it won’t be enough to power the whole world. So, in order to

89% of students admitted to using ChatGPT for assignments according to a study by Forbes yet most scientists who develop AI can’t fully tell you how it works. ChatGPT can write essays, generate creative works, assist in scientific research and have in-depth conversations but yet if you were to

Dive into the uses, mechanisms, and chemistry behind these cutting-edge materials, and the inevitable challenges that such creations might face in practice

Introduction Since around 500 B.C., the ancient Greek civilization introduced one of the earliest forms of democracy. Back then, voters would write their choices on broken pieces of pottery called ‘ostraka’. Imagine a world where the outcome of a major election isn’t just about the number of people

Sanjay Patel and his wife Leslie were involved in the rebuilding of a wind tunnel. That I couldn’t grab a second to ask why indicates the pace of a Sanjay Patel conversation. He’s a whirlwind of insight, brilliance and empathy, his thoughts speeding far ahead of one’s

Floods can devastate cities, but what if we fought water with nature instead of just concrete? While relief channels redirect raging rivers, a quieter revolution is unfolding: re-meandering rivers to slow floods, restore ecosystems, and rethink how we shape the land.

In 1989, a hidden engine defect doomed United Flight 232, killing 112. Decades later, Qantas Flight 32 suffered a similar failure but landed safely. Smarter systems and lessons learned turned potential tragedy into triumph. Two flights, one cause, two very different outcomes.

Quantum batteries could revolutionise energy storage, offering faster charging and higher capacity. While still experimental, early prototypes show promise, potentially transforming how we power electric vehicles and renewable systems.